In a fractious and unruly session last month, parliament passed three laws that some say could pave the way for India to upend the global food trade, while others fear it will wreck the livelihoods of millions of farmers. Within days, rural groups and opposition leaders launched public protests.

The move toward a free market for farm sales goes to the heart of a system that directly affects more than half of the nation’s 1.37 billion people, altering government controls that millions of families have come to rely on, but that have hobbled the nation’s efforts to productively farm one of the largest areas of fertile land on earth. If they succeed, India could not only feed itself, but become a major food exporter.

“We need private sector investment in technology and infrastructure for Indian agriculture to realize its full potential and compete better in the global marketplace,” said Siraj Chaudhry, managing director and chief executive officer of agriculture services company National Collateral Management Services Ltd. But the government must make its intent very clear to win over skeptics. “This is a major policy change that impacts a large and vulnerable section of the population.”

India processes less than 10% of its food production and loses about 900 billion rupees ($12.3 billion) a year due to wastage from inadequate cold storage, said Amitabh Kant, chief executive officer at government think tank NITI Aayog.

Shiromani Akali Dal, a long-term supporter of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, which rarely went against the decisions of Modi’s coalition, quit the government. It said farmers fear the measures will eventually kill the government’s price support regime for crops and leave them at the mercy of big corporations that would control the market.

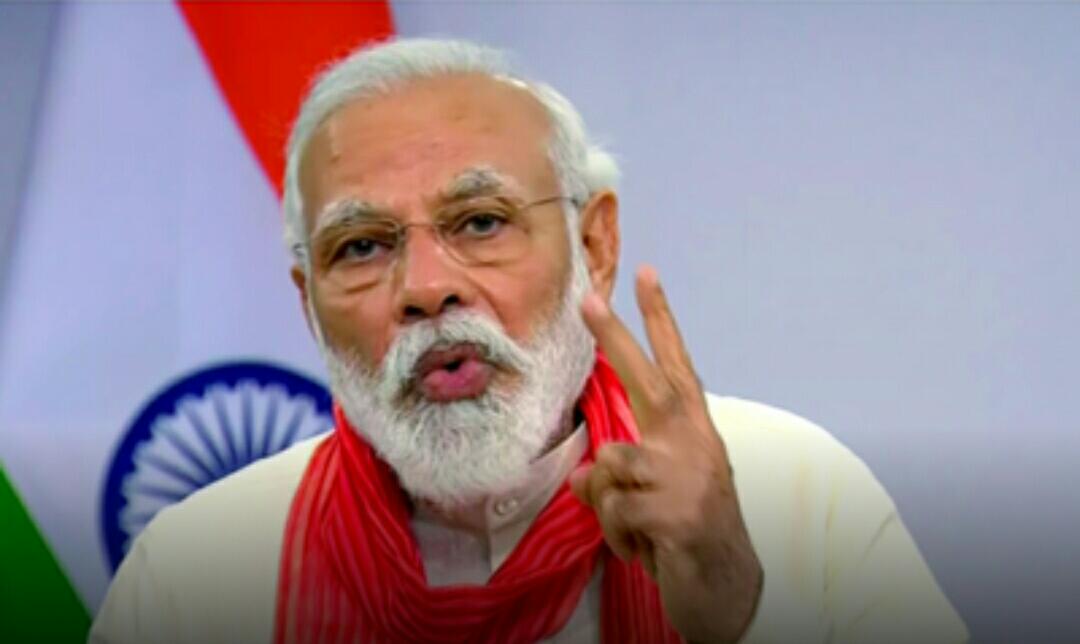

Modi and his ministers say the concerns are baseless and the price guarantee program will continue. His administration even raised some minimum prices for winter crops to try to reassure farmers that the price supports aren’t in jeopardy.

It’s a highly emotive subject in India. The government sets price floors for more than two dozen crops and buys mainly wheat and rice for its welfare programs together with some pulses and oilseeds to prevent distress sales by farmers. The massive subsidies help distribute staples to the poor through a chain of more than 500,000 fair-price shops.

The issue has become even more heated because of the pandemic. The disruption to farms and supply chains has exposed weaknesses in the government welfare system, which is hampered by bureaucracy, underfunding and archaic distribution facilities.

Farmers point out that, while the government’s guaranteed prices are often considered benchmarks, private buyers don’t have to pay them.

“We are disappointed,” said Charanjeet Singh, who grows rice, wheat and vegetables on his farm in the northern state of Haryana. “The government should guarantee that all farmers, irrespective of whether they are selling in the designated grain markets or to private buyers, will get at least the minimum support price.”

Analysts and industry experts say the new policy has the potential to change the face of Indian agriculture, which has been hampered by low yields and inefficient smallholdings, by encouraging more contract farming. That’s a system where private companies agree prices for crops with farmers prior to the harvest or even before sowing, and offer loans, provide quality seeds and encourage mechanization.

The new rules would also make it easier to sell crops in other states or abroad. Farmers would get a more stable income and the increased production would boost exports and revenue, they say.

“Overall, the reforms should benefit farmers and encourage contract farming,” analysts at Motilal Oswal Financial Services Ltd. said in a report. “As private sector participation increases over the years, the Indian agriculture sector’s supply chain and infrastructure would improve.”

Farming has lagged behind other sectors of India’s economy. The rural poverty rate is about 25% compared to 14% in urban areas, according to World Bank data. Underinvestment has made the food supply vulnerable, a fact that is being underlined as the coronavirus spreads across the country.

Food inflation accelerated 9.7% in September as Covid hit the nation’s already fragile supply chains. While supporters of the farm reforms say the changes would make the system more robust in future, others argue that the crisis reinforces the need for a safety net for farmers.

“It will be the end of the road for the food security program,” said Kannaiyan Subramaniam, general secretary of a farmers union in southern India, who grows gooseberries, potatoes and other vegetables. “In the long run, corporations will monopolize trade, production and stockpiles. The government will succumb to pressure from the WTO and get rid of the public grain procurement.”

Before the new amendments, farmers in most states were restricted from selling their crops outside government-facilitated wholesale markets and faced legal hurdles in transporting harvests to other states.

Central to the reforms is an amendment to the Essential Commodities Act, a 1955 law that some say is the root of India’s agricultural inefficiency.

“It was an anti-farmer policy,” said Atul Chaturvedi, president of the Solvent Extractors’ Association of India, which represents vegetable-oil processors. “This one act stymied the growth of Indian agriculture big time.”

When prices rose due to demand, the law’s price-control measures kicked in, discouraging investment to increase production, said Chaturvedi, who is also executive chairman of Shree Renuka Sugars Ltd. The government would also sometimes ban exports of some farm goods to control local prices, as well as limiting the ability to store crops. Farmers suffered huge losses when production, especially of perishable commodities, surged.

Some critics of the amendments to the law say the new situation could be worse for farmers. Corporates and multinational companies buy agricultural products at a cheaper rate and sell at higher prices, “squeezing both ends by hoarding and black marketeering,” said the All India Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee, a farmers’ pressure group. “There is no penalty for failure to honor contracts.”

If the government can push through the reforms while retaining the support of farming communities, it could create a platform for wide-scale improvements in the nation’s food output, The country is already the world’s largest producer of milk and the second-biggest grower of wheat, rice and some fruits and vegetables. It’s also one of the biggest exporters of cotton, rice and sugar.

If India can raise productivity to global norms, the country could become “an important link in global food supply chains,” NITI Aayog’s Kant wrote in a newspaper article. The new reforms, he said, set the stage for India to become “a food-export powerhouse.